In-time submission and academic quality guaranteed.

Find Civil Disobedience Essay

15 samples in this category

Essay examples

Essay topics

Civil disobedience plays an important part in how our society has been shaped up until this moment, it is the act of defying a law by ethics. The term “civil disobedience” was invented by Henry David Thoreau in his 1848 essay to describe how he refused to pay the state...

2 Pages

992 Words

The end of World War Two and the establishment of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights intended to end global injustices and put forth a positive influence on human liberty and dignity; however, the South African policies of apartheid outlined in motion undignified and increasingly oppressive, racially segregated laws – polarising South Africa from the rest of the globe....

Persuasive Essay on Civil Disobedience

2 Pages

1131 Words

Extinction Rebellion is an activist group that pushes for change across the globe through nonviolent civil disobedience. Martin Luther King and Thomas Hobbes both believed that rules should be followed, but believed in two different sets of rules. On the one hand, Martin Luther King argued that if you break an unjust law, you must do so willingly and accept...

Civil Disobedience and Resistance to Civil Government Essay

6 Pages

2962 Words

What are the conditions, if any, that would justify the use of violence to oppose an unjust legal system? Introduction Political resistance continues to manifest in different forms and to varying degrees throughout the modern age. Despite its critics, civil disobedience has generally come to be considered a permissible mode of resistance. The philosophical debate that I seek to engage...

Essay on Civil Disobedience Rhetorical Devices

2 Pages

1021 Words

Civil Disobedience Rhetorical Analysis American transcendentalist and philosopher, Henry David Thoreau, wrote the essay “Civil Disobedience” in response to slavery and Americans' involvement in the Mexican-American War. Thoreau practiced what he preached, spending the night in jail for non-payment of taxes in protest of the Mexican-American War. Throughout his essay, he shares his idea, which is “That government is best...

Civil Disobedience Argumentative Essay

3 Pages

1438 Words

Many people still argue whether the Umbrella Movement is a civil disobedience protest or a riot. The nature of them is different, the former is to fight for the rights and interests of society but the latter is to fight for self-interest and violence is involved. Therefore, seeking the nature of the umbrella movement is conducive to unraveling the argument....

Nonviolence Civil Disobedience: Montgomery Bus Boycott & Sit-Ins

1 Page

671 Words

“One has not only a legal, but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws” - Martin Luther King Jr. Background information strategy used during the 1950-1965, strategy used in North Carolina, and Alabama. Strategy used to get more rights that the black people should have. Strategy used by Rosa Parks,...

Whose Civil Disobedience Inspired MLK: Essay

3 Pages

1383 Words

The refusal to abide by certain laws or to pay taxes, as a nonviolent form of political protesting, is civil disobedience. These types of protests were very common during the 18th century or the Romanticism period of literature. Many civil disobedience acts powered pieces of literature still known to us today, for instance, “On Civil Disobedience” by Mohandas K. Gandhi,...

Essay on Gandhi Civil Disobedience

6 Pages

2537 Words

Developed in the early nineteenth century, transcendentalism was a philosophical movement that arose to pose objections to the general state of spirituality and intellectualism. As fathers of the transcendentalist movement, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson endorsed principles of morality predicated upon higher spiritual laws. They argued that in order to experience personal liberty, one must align themselves with...

Civil DisobedienceMahatma Gandhi

Was the Boston Tea Party an Act of Civil Disobedience? Essay

1 Page

378 Words

Americans nowadays start using the civil rights act as a way to allow the civilians to become free and have equal rights. A recent example of this is when Donald Trump sued the Black Lives Matter Organization because the organizer DeRay Mckensson “did nothing to prevent the violence or to calm the crowd.” The definition of civil disobedience is to...

Boston Tea PartyCivil Disobedience

Civil Disobedience VS Morality

1 Page

404 Words

Nobody has the same morals, beliefs, or even opinions. Morality does not have a true right or wrong because of everyone's individuality. Since everyone has their own opinions, they should have the right to voice those opinions; there are several ways of doing so. As a citizen, an individual with my own beliefs, I believe I have the right to...

Civil DisobedienceMorality

Lessons About Civil Disobedience And Activism By Martin Luther King Jr

1 Page

527 Words

Corruption in legislative issues is the usage of sanctioned controls by government specialists for silly private increment maltreatment of government control for various purposes, for instance, concealment of political enemies and general police mercilessness is in like manner seen as political debasement. Martin Luther King expressed that debasement and shamefulness will never be changed by concealing them however by conveying...

Martin Luther King Jr. And Malcolm X: Protest And Civil Disobedience

6 Pages

2795 Words

For most Americans, the ideological struggle between the Civil Rights and Black Power movements were centered on two individuals, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X respectively. It is also generally socially accepted that Martin Luther’s philosophy prevailed and as such has been held up as the model for enacting social change in America, although often used to criticize the...

Comparison of Civil Disobedience: MLK vs Malcolm X

1 Page

528 Words

How do the ideas of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X illustrate the similarities and differences in their perspective on social civil rights? Dr. King and Malcolm X were both civil rights leaders and they both wanted freedom for all people, but just in a different way. In “Stride Toward Freedom” by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., he...

Martin Luther King’s Views Regarding Civil Disobedience

3 Pages

1518 Words

In this paper, I will argue that Martin Luther King’s views about civil disobedience makes him more reliable compared to Plato’s beliefs because Martin Luther King utilizes emotional language and concrete examples to build his credibility and gain the trust of others. Furthermore, I will discuss Plato and Martin Luther King’s viewpoints about disobeying the law and how each of...

Civil DisobedienceMartin Luther King

Civil Disobedience: Martin Luther King Jr. And Nelson Mandela

3 Pages

1583 Words

Civil Disobedience, also called passive resistance, has its meaning on refusing the to obey the law in a nonviolent act. It was first used by Henry David Thoreau. His ideology was based on disobedience. He believed people can change things by disobeying because it was an act that does not need violence. Henry David Thoreau was born on July 12,...

Civil DisobedienceMartin Luther King

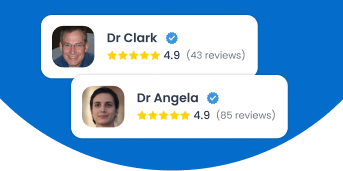

Join our 150k of happy users

- Get original paper written according to your instructions

- Save time for what matters most

Fair Use Policy

EduBirdie considers academic integrity to be the essential part of the learning process and does not support any violation of the academic standards. Should you have any questions regarding our Fair Use Policy or become aware of any violations, please do not hesitate to contact us via support@edubirdie.com.