In-time submission and academic quality guaranteed.

Democracy essays

113 samples in this category

Essay examples

Essay topics

The concept of Democracy has been described as something difficult to categorize, which ultimately led to the concept of polyarchy as a way of standardizing what democracy is to measure and classify different countries as such. This essay will assess how Dahl’s (1973) definition led to a valid measure of...

1 Page

518 Words

Introduction Sara Holbrook's poem "Democracy" is a thought-provoking piece that challenges conventional notions of democracy and raises questions about its true meaning and practice. In this critical essay, we will explore the various themes and techniques employed by Holbrook in her poem, analyzing the underlying messages and implications of her words. Analysis Holbrook's poem "Democracy" is a critique of the...

Jeffersonian Democracy Vs Jacksonian Democracy: Critical Essay

1 Page

606 Words

Introduction: Jeffersonian Democracy and Jacksonian Democracy represent two distinct eras in American political history, each with its own set of ideals, policies, and impacts. While both movements sought to expand democratic principles, they differed significantly in their approaches and outcomes. This essay critically examines the strengths and weaknesses of Jeffersonian Democracy and Jacksonian Democracy, highlighting their contributions to American democracy...

Jefferson Vs Jackson Democracy: Compare and Contrast Essay

1 Page

551 Words

Introduction: The early years of the United States witnessed two influential presidents, Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson, who shaped the political landscape and contributed significantly to the development of American democracy. Although both leaders championed the ideals of democracy, their approaches and policies differed in several key aspects. This essay aims to compare and contrast Jeffersonian democracy and Jacksonian democracy,...

Jacksonian vs Jeffersonian Democracy: A Comparison

1 Page

556 Words

Introduction: Jacksonian Democracy and Jeffersonian Democracy were two distinct political ideologies that emerged during different periods in American history. Both movements had a significant impact on the nation's development and shaped its political landscape. This essay will compare and contrast Jacksonian Democracy and Jeffersonian Democracy, focusing on their views on government, economic policies, and visions for the nation. Body: Views...

Interracial Democracy Essay

1 Page

599 Words

Introduction: Interracial democracy, the vision of a society where individuals from different racial and ethnic backgrounds coexist as equals, has been a longstanding aspiration in societies marked by racial divisions and inequalities. This essay critically examines the concept of interracial democracy, exploring both its challenges and the promise it holds for creating a more inclusive and just society. Body: Historical...

How Is Athenian Democracy Different from Modern American Democracy

1 Page

595 Words

Introduction: Democracy, as a form of government, has evolved significantly over time. Athenian democracy, which emerged in ancient Greece, laid the foundation for modern democratic systems, such as the one practiced in the United States. While both Athenian and American democracies share the principles of citizen participation and popular rule, there are notable differences between the two systems. This essay...

E.B. White Democracy Analysis Essay

1 Page

588 Words

Introduction: E.B. White, a renowned American writer and essayist, is celebrated for his insightful observations on various aspects of life and society. In this critical essay, we will delve into E.B. White's analysis of democracy, exploring his thoughts, criticisms, and perspectives on the concept and its application in American society. Body: Appreciation for Democratic Principles: E.B. White expressed a deep...

DF Wallace's Tense Present: English Democracy & Usage Wars

1 Page

529 Words

Introduction: David Foster Wallace's essay "Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the Wars over Usage" explores the intricacies and controversies surrounding the usage and interpretation of the English language. This critical essay delves into Wallace's arguments, examining his insights on language, democracy, and the ongoing conflicts over linguistic norms. Body: Language and Power: Wallace highlights the relationship between language and power,...

Essay on Are Interest Groups Good or Bad for Democracy

2 Pages

957 Words

In the study of comparative politics, many political theorists such as Andrew Hindmoor, Mark Petracca, and Jon Elson explain political occurrences such as war, voting methods, and the economy through the understanding of Rational Choice Theory. Rational Choice Theory is a prominent theory in the study of Politics and Economics. It posits that individuals, institutions, and societies construct purposive, goal-seeking...

Popular Democracy Definition Essay

1 Page

581 Words

Democracy is the shape of authority in which the ruling strength of a kingdom is legally vested no longer in any unique type or class but in the individuals of the region as a whole. it is an authority in which the will of the majority of residents rules barring overriding the rights of the minority. 'Our charter is named...

Essay on Greek Culture and Democracy

1 Page

520 Words

Originally, Greece was not a country united under one ruler instead it was made up of several hundred poleis or city-states. Each polis was independent and had its political system. Athenian democracy developed around the 6th century in Athens one of the Greek city-states (Wikipedia, n.d). Around 800-500 BCE power and wealth in Athens were concentrated amongst the aristocratic class...

Essay on Nationalism and the Spread of Democracy

1 Page

429 Words

Sweden’s rise in nationalism throughout the centuries was encouraged by movements that protested for religious, labor, and women’s rights. People power plays a crucial role in Swedish society to raise social awareness and political movements. During the 18th century, Sweden had lost the Great Northern War which forced them to make changes to their constitution and introduce the parliament. In...

Essay on Majoritarian Vs Pluralist Democracy

3 Pages

1180 Words

When the Founding Fathers drafted the Declaration of Independence, it was written to protect the new republic from absolute power. Whereas it is being called as the British Monarchy. Furthermore, the Great Compromise allowed states to have an equal voice in the Senate while populous states had a greater presence in the House of Representatives. The Congress who had truly...

Essay on Thomas Hobbes Definition of Democracy

3 Pages

1309 Words

The Oxford dictionary describes democracy as “Democracy is all a system of government where the citizens exercise power by voting”. Democracy existed in pre-agricultural societies, it was first seen in Greece, in Athens in the 6th and 5th centuries BC. Democracy first made an appearance in the form that we know, as representative democracy, in the 18th century, as the...

Appeal of the Democracy of Goods Essay

1 Page

668 Words

Introduction The concept of the democracy of goods suggests that consumer products are accessible to all individuals, regardless of their social or economic background. It implies that material possessions are a measure of personal worth and that everyone has an equal opportunity to acquire them. This critical essay examines the appeal of the democracy of goods, exploring its cultural and...

Essay on Elite Democracy Definition

4 Pages

2006 Words

In 1957, the Treaty of Rome was signed by six countries including Belgium, France, Italy, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, and West Germany, leading to the creation of the European Economic Community and the establishment of a customs union. Those six countries were the founding members of the European Union. Afterward, more treaties and agreements were signed, and eventually, the number of...

Social Media: Enemy of Democracy - Persuasive Essay

1 Page

496 Words

The way social media curves our day-to-day lives is really alarming. Our generation is relying too much on social media platforms, and as a result, we cannot distinguish between what's right and wrong. Social media has made us Americans too gullible, which in turn makes us an easy target for fake news. The use of social media in politics, including...

Education Is a Power to Sustain Democracy and Freedom

2 Pages

1092 Words

In recent discussions of the true power of education, a controversial issue has been whether education is the most powerful means to sustain democracy and freedom. On the one hand, some argue that education is not the most powerful means to sustain democracy and freedom. From this perspective, people see how there could be faults in the educational system and...

Relationship between Democracy and Illiteracy

1 Page

540 Words

Democracy progressively nourishes in the lap of literacy. Democracy without literacy is like the vehicle without wheels. Democracy is the government of the people, by the people, for the people. In this system, people drive the government with the potent of literacy. But illiteracy jams the wheels and derailed the democracy out of the way. However, illiteracy can be rated...

DemocracyIlliteracy

What Did Plato and Aristotle Think of Democracy: Informative Essay

4 Pages

1767 Words

Winston Churchill said that “democracy is the worst form of government – except for all the rest.” Compare and contrast conceptions of democracy in the two theorists we have studied. Democracy is defined as “a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.” The concept of all the citizenry...

Democracy

Roman Republic vs Greek Democracy: Compare & Contrast

7 Pages

3401 Words

1.0 Introduction With the end of the cold war, a new political world order emerged. An order that witnessed the collapse of the former Soviet Union. This was accompanied by the belief in the triumph of Western liberal democracy. Such a belief was made by Francis Fukuyama in his book The End of History and the Last Man. According to...

Democracy

Oligarchy Vs Democracy: Compare and Contrast Essay

5 Pages

2299 Words

In the history of the city-state of ancient Athens, two major coups took place to replace democracy with an oligarchy; the first took place in 411 BCE after the failed Sicilian Expedition and another in 4043 BCE that Sparta installed after the defeat of Athens in the Peloponnesian War. The first instance of evolution from a democracy into an oligarchy...

Democracy

Madisonian Democracy: Definition Essay

1 Page

270 Words

What did Madison see as the primary threat to democracy? How did Madison propose to keep this threat in check? Madison’s argument in Federalist #10 is that we need a republic over a direct democracy due to a group of people having varying interests and desires (factions) that would then be controlled by the majority. Madison stated that in order...

American HistoryDemocracy

Informative Essay on Jacksonian Democracy

1 Page

516 Words

The term “Manifest Destiny” refers to the belief that white Americans must expand across the North American continent and that such expansion was ordained by God. The United States would act as the diffuser of Protestant Christianity and Jacksonian Democracy to as many people as possible. Because of this doctrine, several different presidents, particularly John Tyler and James K. Polk,...

American HistoryDemocracy

Informative Essay on a Bard of Democracy

1 Page

363 Words

Walt Whitman (1819–1892) was the greatest American poet and his classic volume 'Leaves of Grass' was considered both a radical departure from convention and a literary masterpiece. Whitman, who had been a printer in his youth and worked as a journalist while also writing poetry, viewed himself as a new type of American artist. His free verse poems celebrated the...

Democracy

Informative Essay about the Father of Democracy

3 Pages

1410 Words

Was Cleisthenes’ role as a reformer of Athenian political institutions a significant one or not? In this essay, I propose to show the significance of Cleisthenes’ role as a reformer in Athens through his extension of power to the common people which further led to their involvement in political and governmental issues resulting later in the development of democracy. Cleisthenes...

Democracy

Informative Essay about the Birthplace of Democracy

3 Pages

1219 Words

There is no denying the great influence the Ancient Greeks had on the Western world. History remembers Ancient Greece for its monumental contributions to art, and military strategy, and essential for creating the democratic societies that paved the way for our founding fathers. The ways in which these ancient civilizations functioned fascinate historians and philosophers alike. This particular part of...

Democracy

In What Way Was Spartan Government Like a Democracy: Analytical Essay

3 Pages

1334 Words

In Greek Lives, Plutarch allows us to learn about, and understand, the lives of several interesting and important historical figures from Ancient Greece. In these biographies, we learn about their rise, their power, their deaths, and the insight all of these figures had. Of the seven men Plutarch talks about, I found Lycurgus, Cimon, Pericles, and Alexander the most interesting....

Democracy

Importance of Representative Democracy: Critical Essay

2 Pages

1021 Words

Democracy for everyone According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, there are some rules for every citizen around the world. For example, every human is allowed to live free from discrimination. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is seen as one of the milestones in the history of documents. It specifies all the rules for human life. Article 21...

Democracy

Athenian vs American Democracy: Compare & Contrast

7 Pages

3110 Words

Once taking the time to think, one realizes that the ancient Greeks, especially the city-state of Athens, have affected nearly every facet of life. Athenian innovation continues to impact everyday American life. The Athenians are the basis of the American education system. They pioneered mathematics, philosophy, science, and the practice of medicine. Maybe the greatest single idea America learned from...

Democracy

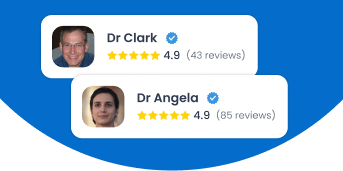

Join our 150k of happy users

- Get original paper written according to your instructions

- Save time for what matters most

Fair Use Policy

EduBirdie considers academic integrity to be the essential part of the learning process and does not support any violation of the academic standards. Should you have any questions regarding our Fair Use Policy or become aware of any violations, please do not hesitate to contact us via support@edubirdie.com.